William Thornton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Thornton (May 20, 1759 – March 28, 1828) was a

The earliest of Thornton's known writings, a journal he began during his apprenticeship, records almost as many entries for drawing and sketching as notes on medical treatments and nostrums. His subjects were most often

The earliest of Thornton's known writings, a journal he began during his apprenticeship, records almost as many entries for drawing and sketching as notes on medical treatments and nostrums. His subjects were most often

In 1789, after briefly practicing

In 1789, after briefly practicing  The painter John Trumbull handed in William Thornton's still "unfinished" revised plan of the Capitol building on January 29, 1793, but the President's formal approbation was not recorded until April 2, 1793. Thornton was inspired by the east front of the

The painter John Trumbull handed in William Thornton's still "unfinished" revised plan of the Capitol building on January 29, 1793, but the President's formal approbation was not recorded until April 2, 1793. Thornton was inspired by the east front of the

As a consequence of winning the Capitol competition, Thornton was frequently asked to give ideas for public and residential buildings in the Federal City. He responded with designs on several occasions during his tenure as a commissioner, less so after 1802 when he took on the superintendency of the Patent Office.

It was during this time he was asked to design a mansion for Colonel John Tayloe. The Tayloe House, also known as

As a consequence of winning the Capitol competition, Thornton was frequently asked to give ideas for public and residential buildings in the Federal City. He responded with designs on several occasions during his tenure as a commissioner, less so after 1802 when he took on the superintendency of the Patent Office.

It was during this time he was asked to design a mansion for Colonel John Tayloe. The Tayloe House, also known as

Architect of the Capitol's official website

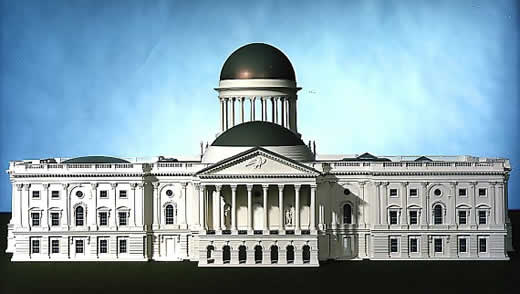

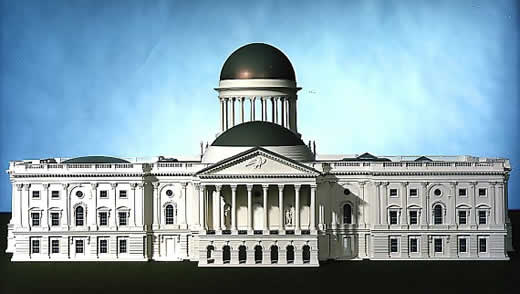

Model Showing Dr. William Thornton's Designs for the Capitol

Tudor Place

Thornton's grave

William Thornton's designs for the United States Capitol

(

British-American

British American usually refers to Americans whose ancestral origin originates wholly or partly in the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, Cornwall, Orkney, and the Isle of Man). It is primarily a demographic or histor ...

physician, inventor, painter and architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

who designed the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill ...

. He also served as the first Architect of the Capitol

The Architect of the Capitol (AOC) is the federal agency responsible for the maintenance, operation, development, and preservation of the United States Capitol Complex. It is an agency of the legislative branch of the federal government and is ...

and first Superintendent of the United States Patent Office

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Commerce that serves as the national patent office and trademark registration authority for the United States. The USPTO's headquarters are in Alex ...

.

Early life

From an early age William Thornton displayed interest and discernible talent in "the arts of design," to employ an 18th-century term that is particularly useful in assessing his career. Thornton was born onJost Van Dyke

Jost Van Dyke (; sometimes colloquially referred to as JVD or Jost) is the smallest of the four main islands of the British Virgin Islands, measuring roughly . It rests in the northern portion of the archipelago of the Virgin Islands, loca ...

in the British Virgin Islands

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = Territorial song

, song = "Oh, Beautiful Virgin Islands"

, image_map = File:British Virgin Islands on the globe (Americas centered).svg

, map_caption =

, mapsize = 290px

, image_map2 = Brit ...

, West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

, in a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

community.Frary (1969), p. 29 where he was heir to sugar plantations. He was sent to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

at age five to be educated. Frary Thornton was brought up strictly by his father's relations, Quakers and merchants, in and near the ancient castle town of Lancaster, in northern Lancashire, England

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashir ...

. There was never any question of his pursuing the fine arts professionally—he was to be trained for a useful life, according to the Quaker ways. Thus, despite the fact that he had a sizeable income, young Thornton was apprenticed for a term of four years (1777–1781), to a practical physician and apothecary

''Apothecary'' () is a mostly archaic term for a medical professional who formulates and dispenses '' materia medica'' (medicine) to physicians, surgeons, and patients. The modern chemist (British English) or pharmacist (British and North Ameri ...

in Ulverston

Ulverston is a market town and a civil parish in the South Lakeland district of Cumbria, England. In the 2001 census the parish had a population of 11,524, increasing at the 2011 census to 11,678. Historically in Lancashire, it lies a few mi ...

, Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

(now Cumbria).

The earliest of Thornton's known writings, a journal he began during his apprenticeship, records almost as many entries for drawing and sketching as notes on medical treatments and nostrums. His subjects were most often

The earliest of Thornton's known writings, a journal he began during his apprenticeship, records almost as many entries for drawing and sketching as notes on medical treatments and nostrums. His subjects were most often flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous) native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' gut flora'' or '' skin flora''.

E ...

and fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. Zoo ...

, but he also did portraits, landscapes, historical scenes, and studies of machinery, such as the Franklin stove, and managed to construct a camera obscura

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a aperture, small hole or lens at one side through which an image is 3D projection, projected onto a wall or table opposite the hole.

''Camera obscura'' can also refer to analogous constructions su ...

. This pattern continued when he enrolled as a medical student in the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

in 1781. He interned at St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by Rahere (died ...

. The architecture of Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, especially that of the New Town

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

that was being built, surely exerted considerable influence. More direct evidence of his interest in architecture is found in the landscapes and sketches of castles he drew while travelling about Scotland, notably in the Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Albania

* Dukagjin Highlands

Armenia

* Armenian Highlands

Australia

*Sou ...

, during these years.

In 1783, Thornton went to London to continue his medical studies; characteristically, he also found time to attend lectures at the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

. The following year he was off to the Continent, carrying a letter of introduction

''Letter of Introduction'' is a 1938 American comedy-drama film directed by John M. Stahl.

In 1966, the film entered the public domain in the United States because the claimants did not renew its copyright registration in the 28th year after pu ...

to Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

, (1706-1790), written by his mentor and distant cousin Dr. John Coakley Lettsome

John Coakley Lettsom (1744 – 1 November 1815, also Lettsome) was an English physician and philanthropist born on Little Jost Van Dyke in the British Virgin Islands into an early Quaker settlement. The son of a West Indian planter and an Irish ...

, (1744-1815).

In the summer of 1784, he explored the Highlands with French geologist Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond

Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond (17 May 174118 July 1819) was a French geologist, volcanologist and traveller.

Life

He was born at Montélimar. He was educated at the Jesuit's College at Lyon and afterwards at Grenoble where he studied law and ...

.

He received his medical degree in 1784 at the University of Aberdeen

The University of Aberdeen ( sco, University o' 'Aiberdeen; abbreviated as ''Aberd.'' in List of post-nominal letters (United Kingdom), post-nominals; gd, Oilthigh Obar Dheathain) is a public university, public research university in Aberdeen, Sc ...

in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

.

Thornton then spent time in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, before returning to Tortola in 1786. There, he saw his mother for the first time since boyhood, where he came face to face with the source of his income—half interest in a sugar plantation and ownership of some 70 slaves, the possession of whom had begun to trouble him.

Eager to achieve fame (and undoubtedly some expiation) in the cause of anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

, he emigrated to the United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

in the fall of 1786, moving to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

. His unsuccessful efforts to lead a contingent of free black Americans to join the small British settlement of London blacks at the mouth of the Sierra Leone River

The Sierra Leone River is a river estuary on the Atlantic Ocean in Western Sierra Leone. It is formed by the Bankasoka River and Rokel River and is between 4 and 10 miles wide (6–16 km) and 25 miles (40 km) long. It holds the major port ...

in West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

were looked on favorably by Philadelphia's Quaker establishment. Some leaders of the new republic—notably James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, with whom he lodged at Mrs. Mary House

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

's prominent boarding establishment in 1787 and 1788—were cognizant of Thornton's abolitionist activities. However, after moving to the City of Washington, he took advantage of slavery. According to a diary his wife kept in 1800, he frequently shopped for slaves and bought and hired them. In 1788, he became an American citizen. Thornton married Anna Maria Brodeau, daughter of a school teacher, in 1790.

Architect

United States Capitol

In 1789, after briefly practicing

In 1789, after briefly practicing medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

and pursuing an interest in steamboats, Thornton submitted a design to the architectural competition for the Library Company of Philadelphia

The Library Company of Philadelphia (LCP) is a non-profit organization based in Philadelphia. Founded in 1731 by Benjamin Franklin as a library, the Library Company of Philadelphia has accumulated one of the most significant collections of hist ...

's new hall. His design won but was somewhat departed from during actual construction. Library Hall was described as the first building in the "modern lassicalstyle" to be erected in the new nation's leading city.

During his visit to Tortola between October 1790 and October 1792, Thornton learned of the design competitions for the U.S. Capitol and the "President's House" to be erected in the new Federal City on the banks of the Potomac. Because a design for the Capitol had not been chosen, he was allowed to compete upon his return to Philadelphia. Between July and November 1792, the Washington administration examined closely the designs submitted by the French émigré architect Etienne Sulpice Hallet, (1755-1825), and Judge George Turner. Hallet and Turner had been summoned to the Federal City in August 1792 to present their ideas to the "Commissioners of the District of Columbia" and local landholders. Both were then encouraged to submit revisions of their designs to accommodate new conditions and requirements. At the beginning of November, Turner's new designs were rejected.

The painter John Trumbull handed in William Thornton's still "unfinished" revised plan of the Capitol building on January 29, 1793, but the President's formal approbation was not recorded until April 2, 1793. Thornton was inspired by the east front of the

The painter John Trumbull handed in William Thornton's still "unfinished" revised plan of the Capitol building on January 29, 1793, but the President's formal approbation was not recorded until April 2, 1793. Thornton was inspired by the east front of the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

, former royal palace later turned art museum, as well as the Pantheon

Pantheon may refer to:

* Pantheon (religion), a set of gods belonging to a particular religion or tradition, and a temple or sacred building

Arts and entertainment Comics

*Pantheon (Marvel Comics), a fictional organization

* ''Pantheon'' (Lone S ...

, famed former Roman temple in Roma and later converted to a Christian church, for the center portion of the design. After more drawings were prepared, enthusiastic praise of Thornton's design was echoed by Secretary of State Jefferson: "simple, noble, beautiful, excellently distributed." For his winning design, Thornton received a prize of $500 and a city lot.

The execution of the design was entrusted to the supervision of Étienne Sulpice Hallet and James Hoban

James Hoban (1755 – December 8, 1831) was an Irish-American architect, best known for designing the White House.

Life

James Hoban was a Roman Catholic raised on Desart Court estate belonging to the Earl of Desart near Callan, County Kilkenny ...

, (1758-1831), (who had also submitted designs for the "President's House - later the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

). Hallet proceeded to make numerous revisions, including removing the rotunda under which Washington was to be enshrined upon his death. So, on September 12, 1794 the President appointed Thornton as one of the three "Commissioners of the Federal District" in charge of laying out the new federal city and overseeing construction of the first government buildings, including the Capitol of which he became supervisor and remained in charge until 1802. Despite important changes and additions, (especially the substitution of a lower copper-clad wooden dome during the 1820s to 1856, for Thornton's original design), especially by second Architect of the Capitol, Latrobe and third Architect Bulfinch, much of the design of the façade of the central portion of the Capitol is his.

Other works

As a consequence of winning the Capitol competition, Thornton was frequently asked to give ideas for public and residential buildings in the Federal City. He responded with designs on several occasions during his tenure as a commissioner, less so after 1802 when he took on the superintendency of the Patent Office.

It was during this time he was asked to design a mansion for Colonel John Tayloe. The Tayloe House, also known as

As a consequence of winning the Capitol competition, Thornton was frequently asked to give ideas for public and residential buildings in the Federal City. He responded with designs on several occasions during his tenure as a commissioner, less so after 1802 when he took on the superintendency of the Patent Office.

It was during this time he was asked to design a mansion for Colonel John Tayloe. The Tayloe House, also known as The Octagon House

The Octagon House, also known as the Colonel John Tayloe III House, is located at 1799 New York Avenue, Northwest in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of Washington, D.C. After the British destroyed the White House during the War of 1812, the house ...

, in Washington, D.C., was erected between 1799 and 1800. It served as a temporary "Executive Mansion" after the 1814 burning of the White House by the British and the house's study was where President Madison signed the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

ending the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

. In 1899 the building was acquired by the American Institute of Architects

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) is a professional organization for architects in the United States. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., the AIA offers education, government advocacy, community redevelopment, and public outreach to su ...

, whose national headquarters now nestles behind it.

Around 1800, he designed Woodlawn for Major Lawrence Lewis (nephew of George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

) and his wife, Eleanor (Nelly) Parke Custis (granddaughter of Martha Washington

Martha Dandridge Custis Washington (June 21, 1731 — May 22, 1802) was the wife of George Washington, the first president of the United States. Although the title was not coined until after her death, Martha Washington served as the inaugural ...

), on of Mount Vernon land. Sometime around 1808, he designed Tudor Place

Tudor Place is a Federal-style mansion in Washington, D.C. that was originally the home of Thomas Peter and his wife, Martha Parke Custis Peter, a granddaughter of Martha Washington. The property, comprising one city block on the crest of Geor ...

for Thomas Peter and his wife, Martha Parke Custis Peter

Martha Parke Custis Peter (December 31, 1777 – July 13, 1854) was a granddaughter of Martha Dandridge Washington and a step-granddaughter of George Washington.

Early life

Martha Parke Custis was born on December 31, 1777 in the Blue Room at M ...

(another granddaughter of Martha Washington).

National Register

Many buildings designed by Thornton have been added to theNational Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

including:

* Library Company of Philadelphia

The Library Company of Philadelphia (LCP) is a non-profit organization based in Philadelphia. Founded in 1731 by Benjamin Franklin as a library, the Library Company of Philadelphia has accumulated one of the most significant collections of hist ...

, 5th & Chestnut Sts., Philadelphia, PA; 1789 (demolished 1887; recreated as Library Hall, American Philosophical Society, 1954)

* United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill ...

, Washington, D.C.; 1793 - exempt

* Prospect Hill, NE of Long Green on Kanes Road, Baltimore, MD; 1796-1798 - added to registry in 1973

* Prospect House, 3508 Prospect Street NW, Washington, D.C. - added in 1972

* Octagon House

Octagon houses were a unique house style briefly popular in the 1850s in the United States and Canada. They are characterised by an octagonal (eight-sided) plan, and often feature a flat roof and a veranda all round. Their unusual shape and app ...

, 1741 New York Avenue, NW, Washington, D.C.; 1799 - added in 1966

* Woodlawn, W of jct. of U.S. 1 and Rte. 235, Fairfax, VA, 1800-05 - added in 1970

* Tudor Place

Tudor Place is a Federal-style mansion in Washington, D.C. that was originally the home of Thomas Peter and his wife, Martha Parke Custis Peter, a granddaughter of Martha Washington. The property, comprising one city block on the crest of Geor ...

, 1644 31st Street, NW, Washington, D.C.; 1816 - added in 1966

Founding of the Washington Jockey Club

In 1802 the Club sought a new site for its track, which at the time lay at the rear of what is now the site of Decatur House at H Street and Jackson Place, crossing Seventeenth Street and Pennsylvania Avenue to Twentieth Street (today theEisenhower Executive Office Building

The Eisenhower Executive Office Building (EEOB)—formerly known as the Old Executive Office Building (OEOB), and originally as the State, War, and Navy Building—is a U.S. government building situated just west of the White House in the U.S. ca ...

,) was being overtaken be the growth of the Federal City. With the leadership of John Tayloe III

John Tayloe III (September 2, 1770March 23, 1828), of Richmond County, Virginia, was a planter, politician, businessman, and tidewater gentry scion. He was prominent in elite social circles. A highly successful planter and thoroughbred horse b ...

and Charles Carnan Ridgely and support of Gen. John Peter Van Ness

Johannes Petrus "John Peter" Van Ness (November 4, 1769 – March 7, 1846) was an American politician who served as a U.S. Representative from New York from 1801 to 1803 and Mayor of Washington, D.C. from 1830 to 1834.

Early life

Van Nes ...

, Dr. William Thornton, G.W. P. Custis, John D. Threlkeld of Georgetown and George Calvert

George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore (; 1580 – 15 April 1632), was an English politician and colonial administrator. He achieved domestic political success as a member of parliament and later Secretary of State under King James I. He lost m ...

of Riversdale, Bladensburg, Maryland, the contests were moved to a new site near Meridian Hill, north of Columbia Road at Fourteenth Street, between present-day Eleventh and Sixteenth Streets. Thornton designed this new track, one mile in circumference, and named the Washington City Race Course. It sat on land leased from the Holmead family, and lasted until the mid-1840s.

Superintendent of the Patent Office

Upon the abolition of the board of Commissioners of the Federal City in 1802,President Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

appointed Thornton the first Superintendent of the Patent Office. When Washington was burned by the British in 1814, Thornton convinced them not to burn the Patent Office because of its importance to mankind. He held the position from June 1, 1802, until his death in 1828 in Washington, DC. During his tenure, he introduced innovations including the patent reissue practice, which survives to this day.

Some of Thornton's reputation as an inventor is due to abuse of his position in the Patent Office.

His improvements to John Fitch's 1788 steamboat are patented but didn't work.

When John Hall applied for a patent on a new breech-loading rifle in 1811, Thornton claimed he had also invented it. As proof, he showed Hall a Ferguson rifle

The Ferguson rifle was one of the first breech-loading rifles to be put into service by the British military. It fired a standard British carbine ball of .615" calibre and was used by the British Army in the American Revolutionary War at the Battle ...

, a British gun dating from 1776, refusing to issue the patent unless it was in his name as well as Hall's name.

Societies

In 1787 Thornton was elected to theAmerican Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

. During the 1820s, Thornton was a member of the prestigious society, Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences

The Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences (1816–1838) was a literary and science institution in Washington, D.C., founded by Dr. Edward Cutbush (1772–1843), a naval surgeon. Thomas Law had earlier suggested of such a soc ...

, who counted among their members former presidents Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

and John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

and many prominent men of the day, including well-known representatives of the military, government service, medical and other professions.

Later life

In the 1820s, Thornton wrote of having been summoned to Mount Vernon in December 1799, in the hopes that he would be able to treat George Washington, but of having arrived after Washington's death; as a result, he devised a plan toresurrect

Resurrection or anastasis is the concept of coming back to life after death. In a number of religions, a dying-and-rising god is a deity which dies and is resurrected. Reincarnation is a similar process hypothesized by other religions, which ...

Washington's frozen corpse by (f)irst to thaw him in cold water, then to lay him in blankets, & by degrees & by friction to give him warmth, and to put into activity the minute blood vessels, at the same time to open a passage to the Lungs by the Trachaea, and to inflate them with air, to produce an artificial respiration, and to transfuse blood into him from a lamb.Thornton's plan was rejected, however, despite "there (being) no doubt in (Thornton's) mind that (Washington's) restoration was possible." Thornton died in 1828 and was buried in

by Mary V. Thompson, at MountVernon.org; retrieved July 6, 2014

Congressional Cemetery

The Congressional Cemetery, officially Washington Parish Burial Ground, is a historic and active cemetery located at 1801 E Street, SE, in Washington, D.C., on the west bank of the Anacostia River. It is the only American "cemetery of national m ...

in eastern Washington, DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan ...

.

See also

*Richard Humphreys (philanthropist)

Richard Humphreys (February 13, 1750 – 1832) was a silversmith who founded a school for African Americans in Philadelphia. Originally called the African Institute it was renamed the Institute for Colored Youth and eventually became Cheyney Unive ...

* John C. Lettsome

Notes

References

* * * *External links

Architect of the Capitol's official website

Model Showing Dr. William Thornton's Designs for the Capitol

Tudor Place

Thornton's grave

William Thornton's designs for the United States Capitol

(

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Thornton, William

1759 births

1828 deaths

Alumni of the University of Aberdeen

American architects

American Quakers

American slave owners

Architects of the Capitol

British abolitionists

British Virgin Islands Quakers

Burials at the Congressional Cemetery

Federalist architects

British emigrants to the United States

American people of British Virgin Islands descent

United States Superintendents of Patents

Quaker abolitionists

Members of the American Philosophical Society

Quaker slave owners

Alumni of the University of Edinburgh